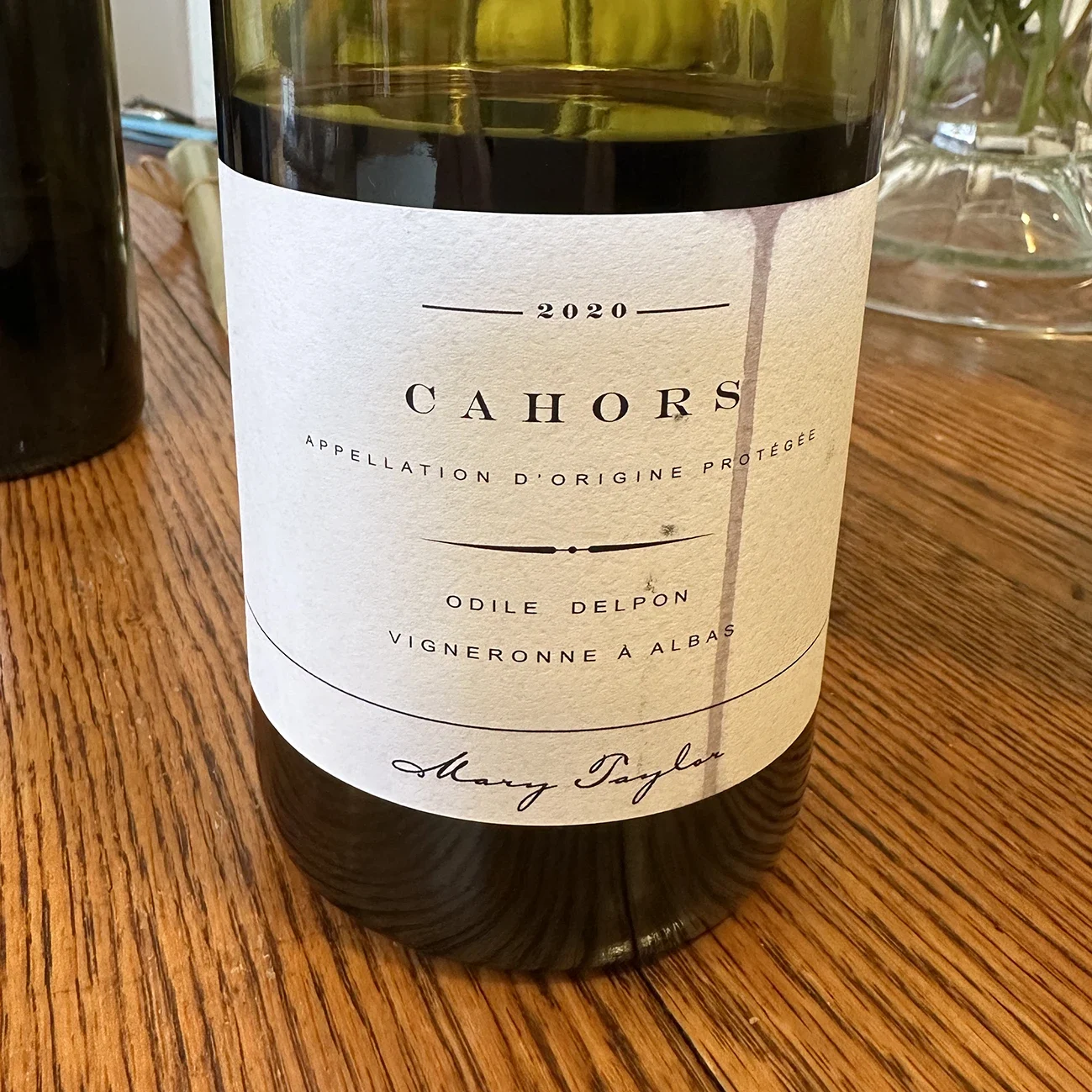

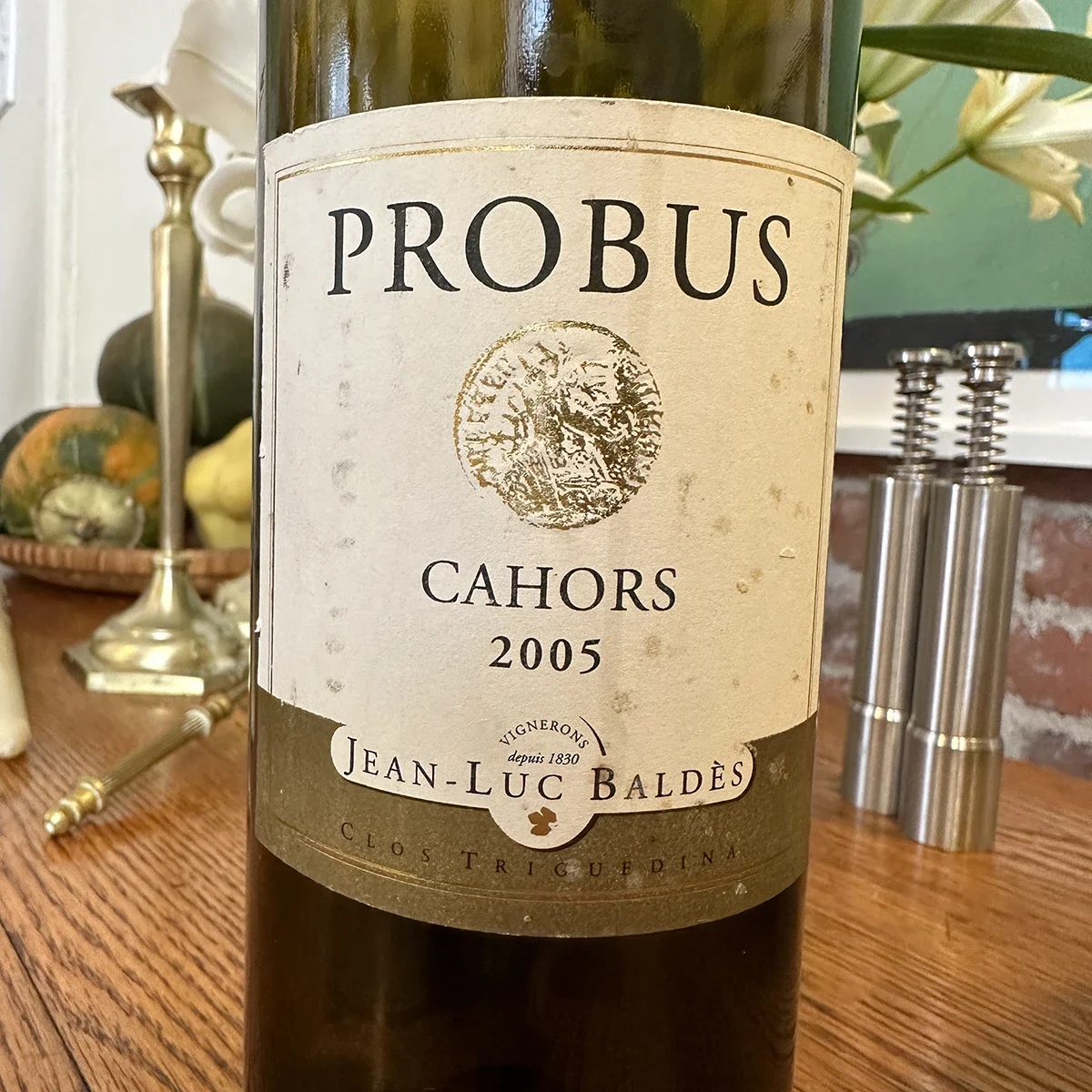

Cahors

Cahors is a famous wine produced from a whopping 10,000 acres of historic vineyards spread to the west of the town of Cahors in southwetern France to the south of Bordeaux. The region only produces red wines, made predominantly from Malbec, which must make up at least 70% of the blend. This is supplemented by Tannat and Merlot if the producer chooses to do so.

Cahors Wines

Cahors is one of the great red wines of southwest France. The wines often have a dense structure and intense fruit. They can be really powerful, but Cahors wines today are often elegant with less marked tannins. It doesn’t mean, though, that they are lightly built. They have intense fruit aromas, often crushed ripe dark berries. A Cahors must be at least 70% malbec, and many are 100% malbec. A maximum of 30% of merlot and/or tannat is permitted. Today, Cahors has around 7,500 acres of malbec.

Wines have been made here since Roman times and the region has a justifiable reputation for producing deeply concentrated, tannic, nearly opaque reds that require bottle age to come around. Indeed the “black wine” of Cahors was coveted around Europe since the Middle Ages. Cuttings of Malbec from Cahors were brought to Argentina in the 1800s and form the base of the Argentine wine industry to this day.

History and viticulture

Known by a variety of Gallic synonyms – Côt, Pressac, Auxerrois – Malbec was once a welcome sight in both the Left and Right Bank regions of Bordeaux. According to wine historians, Malbec was first planted in St-Emilion in the early 18th century, imported by Chateau de Pressac. This ancient property lent its name to the new arrival, which soon promulgated in prestigious sub-regions like Pauillac and Margaux. Although it may sound highly implausible today, Malbec is said to have dominated the vineyards of First Growth Chateau Lafite in the 1700s. By the early 19th century, approximately 60 percent of Bordeaux’s acreage was dedicated to growing Malbec. Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot played a subordinate role to the grape.

The Cahors version of Malbec lives up to its reputation as a brooding, impenetrable heavyweight wine, quite distinct from the early approachability of many Argentine styles. While few examples are exported to the United States, those that are should be sought out by those favoring big, stroppy wines at a reasonable price.

To Cahors and beyond

Winegrowers in Cahors cultivated Malbec vines long before the variety was introduced to the New World. Cahors is the undisputed birthplace of the style, although perhaps ironically, few consumers would actively associate the region with Malbec today. Due to the vagaries of the French appellation system, the variety seldom appears on labels. Referred to as Côt and Auxerrois, Malbec is often blended with small amounts of Tannat and/or Merlot. The resulting wine style may disappoint aficionados of ripe and silky Mendoza Malbec; more tannic, fresher, and higher in acid, French Malbec is a product of the local terroir. After a period of indifference, consumers and sommeliers are starting to appreciate the charms of this particular interpretation of the grape.

Bordeaux

Malbec is one of six permitted red grapes in Bordeaux (all six: cabernet sauvignon, merlot, cabernet franc, malbec, petit verdot, carmenère). But there is not much malbec left in Bordeaux, only 2,200 acres (out of 270,000). Before the extremely severe winter frost in 1956, there were 12,500 acres, but many producers replaced their malbec vineyards with merlot, which is easier to grow. Malbec needs to be fully mature at harvest time not to get too harsh or herbaceous. What is left today in Bordeaux is mainly on the right bank. In the Bourg and Blaye sub-regions, you can find wines with 10% malbec in the blend. The grape is always a bit more tannic here in Bordeaux than in Argentina.

Loire

Malbec thrives in the eastern part of the central Loire, in Touraine, close to all the magnificent royal castles for which the Loire has become world-famous. The grape is found in the following appellations: Rosé de Loire, Touraine, Touraine Amboise, Touraine Azay-le-Rideau, Touraine Chenonceaux and Touraine Mesland. The climate in the Loire Valley is sometimes a bit too chilly for malbec to ripen properly, but sometimes it does, especially if you keep the yields low. The result is often excellent.

Argentina

Malbec is Argentina’s most famous grape variety. Since 1990, the plantations have grown at a record pace and now cover almost 100,000 acres. Argentine malbec has had great success in the United States. Many US consumers believe that the grape originates from Argentina, which is understandable.

The surface area has snowballed. And the Argentinean malbec wines have changed, from fruity unpretentious to something more complex. Today, ambitious producers realize that in certain places, you can obtain higher quality from the grape than in others. Location matters. Argentine malbec is no longer just decent volume wines.

The vineyards planted on higher altitudes, on the Andes’ mountain slopes, benefits from a cooler climate. Traditionally, vineyards have been planted on the plains. At higher altitudes, it is easier to retain the acidity in the wines. The sub-region or the vineyard’s name are emphasized by the growers and sometimes displayed on the label. Sometimes the producer even adds the altitude of the vineyard on the label.

An Argentinian Malbec in the low-price segment is still a smooth, easy-to-drink wine. For a few dollars more, there are many much more “serious”, ambitious and nuanced malbec wines. Spend a little more and you will get much more character.

If we generalize, a South American malbec has more fruit and ripeness, and a French one has more tannins and structure.

Two Times Malbec Is Wiped Out

The “Cahors grape,” which is actually called Malbec, traveled to Argentina in the mid-19th century when French agronomist Michel Aimé Pouget, commissioned by Argentinian governor Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, brought grapevine cuttings from the Cahors region of France to Argentina, where the grape thrived due to the climate and became a staple of Argentinian winemaking

Malbec was revived in France primarily through the region of Cahors, where it is known as “Côt,” where growers continued to plant and cultivate the grape even after it declined in other parts of the country, particularly following phylloxera and frost damage, making it the signature variety of the region and leading to the establishment of Cahors as an Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) in 1971

In 1956, as in Bordeaux, the entire Malbec crop was wiped out by spring frost; unlike Bordeaux, however, growers in Cahors decided to replant Malbec and make it the signature variety, with Cahors becoming an appellation in 1970.

Key points about Malbec’s revival in France:

- Cahors as the stronghold:

While Malbec largely disappeared in other French regions, Cahors remained dedicated to the grape, allowing it to persist and eventually become the only significant area for Malbec production in France. - Phylloxera impact:

The phylloxera outbreak in the 19th century led to widespread replanting of vineyards, and in most regions, growers opted for different varieties instead of Malbec due to its susceptibility to disease and climate challenges. - Recent resurgence:

Although Cahors has always produced Malbec, recent years have seen increased interest in the region and its wines, partly due to the global popularity of Argentinian Malbec, which is also derived from the same grape variety. - Modern winemaking:

New techniques and a better understanding of terroir have helped producers in Cahors create more approachable and appealing Malbec wines

Yet its exact origins are unknown. An often-told romantic tale involves a Hungarian traveler who introduced the grape to France in the Middle Ages. A more realistic explanation is that Malbec is indigenous to France, probably originating in northern Burgundy. It established a foothold in the vineyards south of the Garonne in the 18th century, in addition to Côtes de Blaye and Côtes de Bourg in Bordeaux.

Winemaking

In recent years, certain winemakers in Argentina and France have been reconsidering their approach to Malbec. They’ve been easing up on the extraction and oak maturation, focusing on bringing elegance and freshness to the fore. Plenty of concentrated and ripe styles are still being made, but the palate has diversified. The net result is that Malbec comes in many different expressions today, from medium-weight beauties to powerfully structured monoliths.

However, all oenologists are united in their belief that only hand-harvested grapes grown in superior soils can yield exceptional Malbec. The top priority is usually tannin management, ensuring that there are no harsh or astringent elements on the finish while there is enough structure to facilitate bottle aging. It is said that the optimal harvest window is very short – typically 3-5 days – if you want to pick top-quality grapes. If the fruit is left on the vine, there is the risk of unwieldy alcohol, a lack of freshness, and acidity.

Grape bunches are often destemmed, although there are various attitudes regarding whether a certain percentage of whole bunches should be used. The favored vessels are stainless steel or concrete, fermented at relatively high temperatures for about 3-4 weeks. Pigeage (punch down) is a popular method to extract fine tannins. Winemakers champion prolonged fermentation to encourage a supple mouthfeel and soft texture, two qualities consumers love in their Malbec.

But the most crucial stage is undeniably maturation before bottling. Many of the most expensive cuvées were traditionally aged in new French oak for at least 12 months, although this approach has slightly fallen out of fashion recently. Instead, aging in concrete and amphora is now in vogue. Winemakers argue that amphora encourages a more pure expression of Malbec, with elegant tannins and no excessively oaky characteristics such as vanilla and cedarwood. As a result, Malbec wines matured in concrete amphora are among the finest being made today.

Topo:

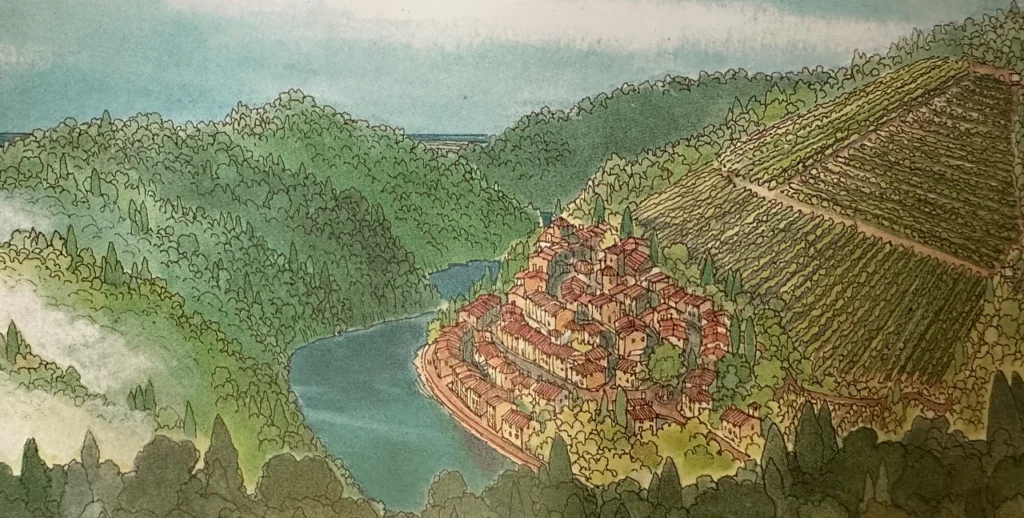

The Cahors region in southwest France is characterized by a rolling hill topography, primarily defined by the winding Lot River valley, with a mix of limestone plateaus (“causse”) at higher altitudes and lower, terraced lands along the riverbanks, creating diverse microclimates and terroir variations due to the river’s sharp bends and gentle slopes; the town of Cahors itself sits on a rocky peninsula formed by a meander of the Lot River

Climate

Most of the vineyards are located on the gravel terraces within the meanders formed by the river Lot. The lowest terrace is too close to the river and therefore not suitable for viticulture; vineyards have only been established on the second, third, and fourth terraces. There is increasing interest in the plateau (technically the fourth terrace) for viticulture called “Les Causses”.

The climate of Cahors is mainly influenced by the Atlantic Ocean, with hot summers and wet winters. In contrast to Bordeaux, it also is influenced by the Mediterranean Sea. The river Lot is an important factor for the microclimate in the vineyards, especially as the nearby Massif Central may occasionally cause severe frost in winter.

The geology of the Cahors region of France includes limestone plateaus, phosphate mines, and the Lot River valley, which all contribute to the region’s wine production and other geological features:

- Limestone plateaus

The Causses are limestone plateaus that form the foundation of the Cahors vineyard. The plateaus are made of Kimmeridgian limestone, a soil type also found in Burgundy’s Chablis. The plateaus also contain iron-rich clays and rare blue clay.

Broadcast Episode/Cahors

Search by category or topic

Cheese Pairings

Coming Soon

Food Pairings

Coming Soon