Chianti

Chianti’s history spans millennia, beginning with Etruscan viticulture in the 8th century BCE and Roman refinement. A major development was the 1872 “recipe” for Chianti by Baron Bettino Ricasoli, which defined the blend of Sangiovese, Canaiolo, and Malvasia Bianca, while the modern Chianti Classico denomination was established in 1932. The iconic Black Rooster symbol originates from a medieval legend about the rivalry between Florence and Siena to define the region’s borders.

Chianti Tuscany Wines

Ancient origins

Etruscans:

The earliest viticulture in the region began with the Etruscans around the 8th century BCE.

Romans

The Romans continued and refined these practices, helping to popularize Tuscan wines throughout their empire

Medieval and Renaissance periods

Black Rooster legend

In the 13th century, a legend arose about a contest between Florence and Siena to settle a border dispute. Each city sent a knight to ride at dawn, signaled by a rooster. The Florentines’ black rooster crowed earlier, allowing their knight to claim a larger portion of the Chianti territory for Florence, leading to the Black Rooster becoming the symbol of Chianti Classico.

Wine as currency

During the Renaissance, wine was a vital part of Florence’s economy and culture.

Earliest mention

The first documented mention of Chianti wine was in 1398.

Modern era

Baron Ricasoli’s recipe

In 1872, Baron Bettino Ricasoli established the formula for modern Chianti Classico, which favored a blend of primarily Sangiovese, with Canaiolo and a small amount of Malvasia Bianca.

Geographical expansion

A 1932 decree expanded the Chianti production zone to a larger area and created sub-zones. The original, historic territory was given the right to use the suffix “Classico”.

Consortium and symbol

The Consortium for the Defense of the Typical Wine of Chianti and its historic zone of origin was founded in 1924, officially adopting the Black Rooster as its symbol.

DOCG status

In 1996, Chianti Classico became its own autonomous Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG), or protected designation of origin

History

Early history to the Renaissance

The early history of Chianti is very much intertwined with the history of the entire Tuscany region. The history of viticulture in the area dates back to its settlements by the Etruscans in the eighth century BC. Amphora remnants originating from the region show that Tuscan wine was exported to southern Italy and Gaul as early as the seventh century BC before both areas begun to actively cultivate grape vines themselves. From the fall of the Roman Empire and throughout the Middle Ages, monasteries were the main purveyors of wines in the region. As the aristocratic and merchant classes emerged, they inherited the sharecropping system of agriculture known as mezzadria. This system took its name from the arrangement whereby the landowner provides the land and resources for planting in exchange for half (“mezza”) of the yearly crop. Many landowners in the Chianti region would turn their half of the grape harvest into wine that would be sold to merchants in Florence. The earliest reference of Florentine wine retailers dates to 1079 with a guild for wine merchants being created in 1282.

In the Middle Ages, the villages of Gaiole, Castellina and Radda located near Florence formed as a Lega del Chianti (League of Chianti) creating an area that would become the spiritual and historical “heart” of the Chianti region and today is located within the Chianti Classico Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG). In the 13th century, the earliest incarnations of Chianti was a white wine. The Florentine merchant Francesco di Marco Datini sold one of the earliest examples of Chianti wines and it was indeed a white.

Unlike France or Spain, Italy did not have a robust export market for its wines during the Middle Ages. Its closest trading partners, France and Austria, were separated from Italy by the massive Alps Mountains and also had ample supply of their own local wines. The English had little interest in Italian wines at this point, finding plenty of sources in France, Spain and later Portugal to quench their thirst. While the sweet Lacryma Christi from Campania had some presence on the international market, most Italian wines had to compete for taste of the local market. Even then this market was mostly limited to the aristocracy (who seemed to preferred strong wines made from Vernaccia or sweet Aleatico and Vin Santos) since outside of the major cities of Rome and Naples, there was not yet a strong middle class.

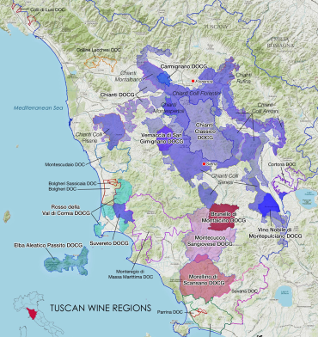

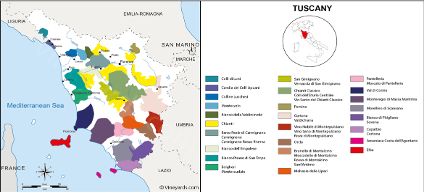

As the wines of Chianti grew in popularity other villages in Tuscany wanted their lands to be called Chianti. The boundaries of the region have seen many expansions and sub-divisions over the centuries. The variable terroir of these different macroclimates contributed to diverging range of quality on the market and by the late 20th century consumer perception of Chianti was often associated with basic mass-market Chianti sold in a squat bottle enclosed in a straw basket, called fiasco.

In addition to changing boundaries, the grape composition for Chianti has changed dramatically over the years. Baron Bettino Ricasoli, the future prime minister in the Kingdom of Italy created the first known “Chianti recipe” in 1872, recommending 70% Sangiovese, 15% Canaiolo and 15% Malvasia bianca. Ricasoli choose Sangiovese to be the base of Chianti because it provided the most aromatics. Canaiolo brought fruitiness to the wine that soften the tannins of Sangiovese without lessening the aromatics. The addition of the white wine grape Malvasia was to provide further softening. Wine expert Hugh Johnson noted that the relationship that Ricasoli describes between Sangiovese and Canaiolo has some parallels to how Cabernet Sauvignon is softened by the fruit of Merlot in the traditional Bordeaux style blend. Ricasoli continued with his winemaking endeavors until 1848 when his wife died. Stricken by grief, he had little desire for his vineyards or his wine. During this time the tides of the Risorgimento were growing stronger and Ricasoli found himself in the political arena which would eventually lead to him becoming the Prime Minister of Italy.

However some producers desired to make Chianti that did not conform to these standards-such as a 100% variety Sangiovese wine, or all red wine grape varieties and perhaps with allowance for French grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot to be used. A few producers went ahead and made their “chianti” as they desired but, prohibited from labeling, sold them as simple vino da tavola.

Despite their low level classifications, these “super Chiantis” became internationally recognized by critics and consumers and were coined as Super Tuscans. The success of these wines encouraged government officials to reconsider the DOCG regulations with many changes made to allow some of these vino da tavola to be labeled as Chiantis.

20th century to modern day

The 20th century saw peaks and valleys in the popularity of Chianti and eventually led to a radical evolution in the wine’s style due to the influence of the “Super Tuscans”. The late 19th century saw oidium and the phylloxera epidemic take its toll on the vineyards of Chianti just as they had ravaged vineyards across Europe. The chaos and poverty following the Risorgimento heralded the beginning of the Italian diaspora that would take Italian vineyard workers and winemakers abroad as immigrants to new lands.[4] Those that stayed behind and replanted, chose high yielding varieties like Trebbiano and Sangiovese clones such as the Sangiovese di Romagna from the nearby Romagna region. Following World War II, the general trend in the world wine market was for cheap, easy-drinking wine, which saw a brief boom for the region. With over-cropping and an emphasis on quantity over quality, the reputation of Chianti among consumers eventually plummeted. By the 1950s, Trebbiano (which is known for its neutral flavors) made up to 30% of many mass-market Chiantis.[2] By the late 20th century, Chianti was often associated with basic mass-market Chianti sold in a squat bottle enclosed in a straw basket, called fiasco. However, during this same time a group of ambitious producers began working outside the boundaries of DOC regulations to make what they believed would be a higher quality style of Chianti. These wines eventually became known as the “Super Tuscans’.

Classification of Chianti

Chianti

Standard Chianti contains a minimum of 70% Sangiovese grapes. The remaining 30% is typically a blend of Merlot, Syrah, and Cabernet though regional grape varieties such as Canaiolo Nero and Colorino may be found as well. These wines have the shortest aging period before release, typically three to six months.

Chianti Classico

Chianti Classico consists of at least 80% Sangiovese. The remaining 20% (or less) is often a blend of the other red grapes mentioned above. Classico is aged a minimum of ten to twelve months before being released. To be labeled Classico, the grapes must come from the Classico district. This is the wine that carries the famous gallo nero or black rooster seal. Since 2006, white grapes previously mandated for Chianti wine have been outlawed in the production of any Chianti that bears the Classico designation.

Chianti Riserva

Chianti Riserva undergoes a longer aging process of 24 to 38 months. That extra time mellows the tannins in the wine and adds greater complexity and structure.

Chianti Superiore

Featuring Sangiovese grapes grown outside the Classico district, Chianti Superiore undergoes a minimum of nine months of aging. These wines also generally come from lower yields.

Gran Selezione

Created in 2014, Chianti Gran Selezione features grapes from the best estate vineyards. These wines undergo at least 30 months of aging before being released. These are some of the highest-quality Chiantis available.

Details of The Black Rooster Legend

In an era when the city-states of Florence and Siena were locked in constant war, they devised a unique resolution: a race dictated by the crow of a rooster. Each city-state would have a knight leave from their respective cities at the first crow of their rooster at dawn. The area where these two knights met would then determine the new boundaries, with each city claiming the land their knight had covered.

Florence, in a clever maneuver, chose a black rooster and deliberately starved it, keeping it in darkness. This unusual strategy paid off when the famished and disoriented rooster crowed long before actual dawn. The Florentine knight, benefiting from this early start, covered more ground, enabling Florence to claim a larger portion of the Chianti region. This clever strategy is commemorated by the Black Rooster emblem on Chianti Classico bottles.

Tuscany Geology

Tuscany’s geology, including a mix of marine sediments, limestone, clay, and shale, creates diverse soils like galestro and alberese, which are crucial for its wine production, particularly the flagship Sangiovese grape. These soil types influence flavor, structure, and quality, while topography shaped by uplift and erosion creates varied microclimates and elevations that further diversify the wine profiles across regions like Chianti, Montalcino, and Montepulciano.

1. Chianti

Presentation of the Sub-Region’s Wines: Chianti is one of Tuscany’s most well-known wine regions, recognized for its elegant red wines made primarily from **Sangiovese**. It is divided into several sub-zones, each offering unique characteristics.

Terroir, Climate, and Geography

Chianti’s landscape is defined by rolling hills that range between 200 to 800 meters in elevation. The soils vary from **galestro** (a crumbly marl) to **alberese** (limestone-rich), contributing to the structure and minerality of the wines. The climate is warm Mediterranean with significant diurnal temperature variations, promoting the slow, balanced ripening of grapes. The combination of warm days and cool nights enhances the acidity and aromatic profile of the wines, giving them freshness and complexity.

Main Wines

Chianti Classico

Made predominantly from Sangiovese, showcasing red cherry, plum, and herb flavors, with lively acidity and structured tannins. Aged in oak for added complexity.

Chianti Riserva

Aged for a longer period, with deeper flavors of dark fruit, tobacco, and spice, showing well-integrated oak notes.

2. Montalcino

Presentation of the Sub-Region’s Wines: Montalcino is celebrated for producing **Brunello di Montalcino**, one of Italy’s most prestigious wines, made exclusively from **Sangiovese Grosso** (locally known as Brunello).

Terroir, Climate, and Geography:

Montalcino is located on a hill that rises up to 564 meters above sea level, providing various microclimates. The soils range from limestone and clay to volcanic and marl, contributing to the complexity and depth of the wines. The region experiences a warm, dry climate, ideal for ripening **Sangiovese Grosso**. The altitude provides cooling influences at night, which helps maintain acidity and balance in the wines.

Main Wines

Brunello di Montalcino

100% Sangiovese Grosso, showcasing black cherry, blackberry, tobacco, and earthy flavors, with firm tannins and excellent aging potential.

Rosso di Montalcino

A younger, fresher version of Brunello, with red fruit, moderate tannins, and a shorter aging period.

Cheese Pairings

Pecorino Toscano

Fontina

Asiago