Rioja

The name “rioja” corresponds to the river Oja, or Rivalia that would be translated as “land of streams”; or, it its origins could lie in the Basaque words herria and ogia, or “land of bread”.

Rioja Wines

Wine Regions

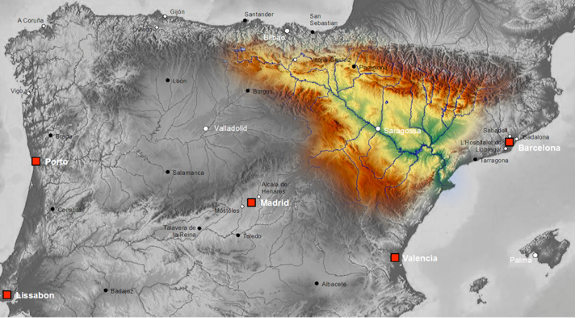

The wine producing region is divided into 3 sub-regions: Rioja Alta, Rioja Alavesa and Rioja Oriental (this name was recently changed from the name Rioja Baja) . Rioja Alavesa is located North of the Ebro river and coincides with the part of Rioja which belongs to the Spanish Basque Country. Rioja Baja is located southeast of Logrono, whilst Rija Alta is located from Logroño to Haro, South of the Ebro river.

In order to add to this complex reality, the wine producing region of Rioja is spread in 3 administrative regions of Spain: Navarre, Rioja and Basque country.

Tempranillo is Rioja´s main grape and most wines are blended with smaller amounts of Garnache, Graciano and Mazuelo grape.

There are four categories characterized by the amount of ageing required:

Crianza Rioja wine

These wines need to stay at least 2 years before they are released to the market. They must stay at least one year aging in an oak barrel (the remaining year would be in the bottle)

Reserva Rioja wines

They must stay at least 3 years in the winery and one of these must be aging in oak barrel.

Gran Reserva

At least 24 months in oak barrel and at least 48 months in the winery before they are released to the market.

Joven or young rioja wine

many winemakers produce wines that may not comply with any of the other categories of Crianza, Reserva or Gran Reserva.

Wine Characteristics

Rioja wines are complex, balanced wines, predominantly red and made from Tempranillo, characterized by ripe red fruit flavors like cherry and plum, and secondary notes of vanilla, spice, and tobacco from oak aging. They range from modern, fruit-forward styles to traditional, more savory, cedar-influenced wines, and are known for their excellent value and aging potential.

Flavor & Aroma Profile

Fruit

Notes of cherry, plum, and sometimes fig or other ripe red fruits are common.

Oak Influence

Aging in American or French oak introduces vanilla, coconut, and dill aromas.

Savory Notes

Tobacco and leather can develop with extended aging.

Balance

The wines exhibit a harmonious balance of fruit, acidity, and tannins.

Structure

Body

Medium to full-bodied.

Acidity

Medium-high acidity, which can be higher in sub-regions like Rioja Alta and Alavesa.

Tannins

Medium-high tannins, providing structure and aging potential.

Aging and Styles

Aging Classifications:

The region’s aging classifications indicate the duration of barrel and bottle aging:

- Joven (Young): Minimal aging, best for early consumption.

- Crianza: Aged longer, offering more pronounced fruit and oak notes.

- Reserva: Significantly longer aging in both oak and bottle, developing more complex, tertiary flavors.

- Gran Reserva: The longest aging periods, resulting in the most complex and savory wines.

Oak Types:

Traditional Riojas use American oak, which adds vanilla and coconut, while modern producers may incorporate French oak for a more subtle influence.

Sub-Regional Differences:

- Rioja Oriental (formerly Rioja Baja): Known for richer, fuller-bodied, and more fruit-forward wines.

- Rioja Alta & Rioja Alavesa: These cooler, higher-elevation areas produce more elegant wines with higher acidity and tannins.

Key Characteristics

Value

Rioja wines are recognized for offering excellent quality for their price, especially when compared to wines of similar age from other regions.

Aging Potential

Many Riojas, particularly Reservas and Gran Reservas, have exceptional aging potential, developing complex characteristics over time

History

The earliest record of winemaking in Rioja, Spain, is from the 11th century B.C., when the Phoenicians settled the region. Local populations have made wine almost continuously since then – for over 3,000 years. Prehistoric dolmens have been found at the foot of the Sierra de Cantabria — ancient funerary monuments from ancient times containing evidence of vessels used to transport and drink wine.

The Romanization of the Iberian Peninsula in the 2nd century B.C. favored vine cultivation and wine production in the region. Remains of local amphorae filled with Rioja wine, transported by galleys sailing the Ebro River, have been discovered. Large cellar facilities found in various locations attest to the importance of wine in the economy of the time.

The Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were a crucial period in the history of Rioja wine. The first documented mention of the word ‘Rioja’ is found in 1099, when the region experienced the confluence of both Arab and Christian cultures. The creation of monasteries, such as San Millán, Valvanera, Nájera, and Albelda, boosted wine production in the region. Some of these monasteries became significant vineyard and cellar owners, thanks to the donations of the faithful. The Camino de Santiago, which attracted thousands of pilgrims from all over Europe, also played a vital role in the wine trade. The pilgrims brought knowledge and technology with them, thus fostering the trade of goods, including Rioja wine, which was found on the main route to Compostela.

The New World

The 19th century, new winemaking techniques in the style of Bordeaux were introduced, as well as oak barrels for aging. Two local landowners, the Marqués de Riscal and the Marqués de Murrieta, influenced by their time in Bordeaux, played a fundamental role in producing soft and robust wines capable of withstanding long journeys.

Climate

While Rioja’s geography isn’t conducive to wine exports, the climate is excellent for production. As a result, most of Rioja’s wine was consumed by residents or pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago until the 1800s. A series of technological advances and ecological disasters from the 18th century to the late 20th century helped to not only improve the longevity of Rioja’s wine but also make it one of Spain’s most famous wine regions.

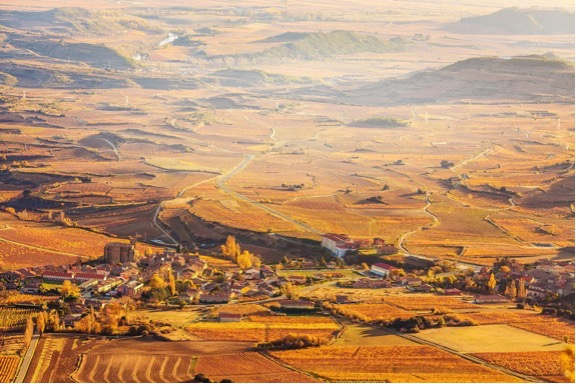

The climate of the QDO Rioja is defined as temperate, the result of the interaction between the Atlantic and Mediterranean climates, with an average annual temperature of 12-14 degrees Celsius and warm summers, contrasting with cool winters. Rainfall is evenly distributed throughout the year, with wet winters and springs and dry summers and autumns. The region enjoys around 2,000 hours of sunshine per year, benefiting the growth of the vines.

The diversity of microclimates is due to the fact that the region stretches about 100 km from north-west to south-east. The eastern areas are more influenced by the Mediterranean climate, while the western areas are more influenced by the Atlantic. With an altitude of between 300 and 900 metres, the vineyards experience a wide range of temperatures, while the proximity of the Ebro River and its tributaries, together with the winds from the valley, cool the area. The warm, dry months of September and October provide optimal conditions for harvesting and ripening.

History of Wine Making

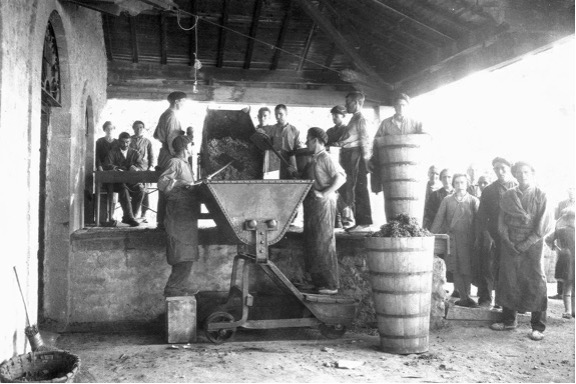

Until the 1700s, wine in Rioja was produced by stomping grapes in stone troughs. It was stored underground in often imperfectly sealed amphorae, and its exposure to oxygen meant the wine often either quickly spoiled or turned to vinegar. The small amount of wine that was exported had to be packaged in leather canteens called bota bags. They were branded with a seal that signified that the wine was made in Rioja from only local grapes.

The first attempt to improve winemaking in the region was made by Don Manuel Esteban Quintano Quintano, a Rioja resident who journeyed to Bordeaux to learn how to produce wine that tasted great, traveled well and improved with age.

One of the most important techniques he learned was to age wines in oak barrels to smooth its flavor and help protect it from spoilage. Soon, it was possible to ship wine as far as the Americas, but the expensive oak barrels fell out of favor in Spain due to area regulations.

Oak barrels were reintroduced by Luciano Murrieta y García-Ortiz de Lemoine nearly a century later. Like Don Manuel, he noted that the wines of Rioja weren’t quite as good as the wines of Bordeaux. So, he traveled to Bordeaux to learn how the winemakers created such delicious and transportable wine. While these innovations improved the longevity of Rioja’s wine, it didn’t make transport easier. It wasn’t until the completion of a rail system in the mid-19th century when Rioja was finally connected to two important port cities, Irun and Bilbao.

The railway coincided with two other ecological events in the mid-1800s. The first was an outbreak of fungus, called powdery mildew, in the vineyards of Galicia, one of Spain’s other winemaking regions. Powdery mildew weakened the vines it infected and reduced grape harvests, which impacted winemaking. Rioja’s vineyards were largely unaffected, and it began to fill the gaps left by Galicia’s faltering wine production.

Then, in 1863, the phylloxera epidemic hit France. Many winemakers moved to Rioja. Their expertise contributed to the region’s exploding popularity. The boom lasted until phylloxera arrived in Spain at the end of the 19th century. By then, however, it had been discovered that vines could be protected by grafting them onto American rootstock, which had resistance to the louse. By grafting American vines onto their own, the winemakers of Rioja were able to avoid the devastation that stuck the French wineries.

Just when it looked like Rioja’s winemakers could breathe easy, World War I (1914–1918) decimated European markets. Then, in 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out and vineyards throughout the country were neglected or destroyed. The war’s end offered little respite. Severe food shortages caused many of the remaining vineyards to be torn up to grow crops.

Spain’s wine industry didn’t begin to recover until the European markets reopened after World War II (1939–1945). And it wasn’t until the 1970 vintage, a legendary one for Rioja, that international consumer interest was reignited in Spanish wines.

Soils:

Rioja has a wide variety of landscapes, including mountains, terraces and valleys, which contribute to soil diversity. When assessing the capacity of soils to produce exceptional wines, it is essential to consider a number of different factors such as altitude, slope, orientation, structure, organic matter, pH, among others. In addition to these factors, it is also crucial to take into account the particular microclimate of the area, as well as the agricultural practices applied in vine cultivation.

- Calcareous clayey soils, characterized by their yellow-ochre color, are poor in organic matter but rich in calcium. Due to the irregular topography of the area, they are difficult to drain and their cultivation is complicated. The roots of the vines penetrate the soil to a depth of about one meter, where they encounter a fragmented rocky subsoil.

- Ferrous clay soils predominate in the middle hills and in the higher areas separating the alluvial terraces of Rioja Alta and Rioja Oriental. These reddish-brown soils are usually deep and very compact due to their high clay content.

- Alluvial soils are mainly located on the banks of the river Ebro and in the valleys formed by its tributaries, forming flat terraces. These sandy and stony soils allow deep roots to penetrate. Their characteristics favor good drainage, while at the same time they accumulate heat and reflect sunlight, creating a favorable environment for the grapes to ripen.

Cantabrian mountains

The Picos de Europa are part of the Cantabrian Mountains, a mountain range in northern Spain that extends for about 300 miles along the northern coast. Located in the autonomous communities of Asturias, Cantabria, and Castile and León, the Picos de Europa are the highest and most dramatic part of this larger mountain chain. The Picos de Europa are a distinct cluster of high limestone peaks, noted for their dramatic, lunar-like landscapes, deep valleys, and diverse scenery, including meadows and mountain farms. The origin of the name can be traced back to ancient times when this mountainous region was inhabited by various peoples, including the Cantabri, an ancient Celtic tribe. The Cantabri were known for their resistance against Roman invasions and their rugged way of life in the mountains

Search by category or topic

Cheese Pairings

Manchego

Idiazabal Dop

Murcia Al Vino Pdo

Mahon Pdo

Food Pairings

Escalivada

Catalan Roasted Vegetables)

A beautiful dish of sweet peppers, eggplant, onion – and other seasonal vegetables if you wish – all flavored with deep roasting, olive oil and garlic, and a lovely light vinaigrette.

Cut the peppers, eggplants and onion in thick strips. Lay out on a rimmed sheet pan, leaving some space between the slices. Drizzle generously with olive oil, coating them well.

Place the sheet pan in a 400 degree oven and bake uncovered until the vegetables are quite soft and their skins well blistered, about 45 minutes. Remove the pan and cover the vegetables loosely with a kitchen towel. Leave to cool for 10- 15 minutes.

When the vegetables are cooled, if you wish to remove the eggplant skins, with a large spoon scoop the pulp. Remove the charred skin from the onions.

Mix together minced garlic, sherry vinegar, paprika, Aleppo pepper and olive oil in a small bowl. Whisk together and then pour mixture over vegetables. Toss again.

Leave to rest at least 1 hour before serving, and preferably overnight. Serve on a platter garnished with parsley and basil leaves, alongside grilled sausages, sharp cheeses and crusty bread.